These my brand-new reflections on geopolitics present it as a philosophical field, emphasizing the influence of geography on political strategies and the impact of geopolitical actions on collective identities and human conditions. It integrates classical philosophical thoughts on power and State acts, aiming to deepen the understanding of nations’ strategic behaviours and ethical considerations. This reflective approach seeks to enhance insights into global interactions and the shaping of geopolitical landscapes.

The Geo-Philosophy

Part II

The phase of the maintenance of our form of civilization unfolds between two apparently opposite and incompatible moments: synthesis and desynthesis. However, the “expansion” of the system has ultimately led to an irreversible crisis. The “crisis” of the West is not due to the incursion of an allotropic element, but to the simple fact that, through expansion, the political grinds down all that is non-political, the metropolis relentlessly grinds down the provincial and the peripheral, urbanism swallows the countryside, the forest, the mountain…, the philosophical absorbs all that is non-philosophical (literature, art, cinema, television, the dream, madness…)—philosophy even amuses itself by producing its own deconstruction; while History grinds down all that is extra-historical, from peoples without history to the history of that which, not unfolding “in public,” would strictly be without history. Now, this expansion has resulted in what Baudrillard calls “implosion,” that is, the “chemical” suspension of all classic opposition in a solution of reversibility or random aggregation, or anyway, according to laws not reducible to any known reference. Such a suspended state is what I call “desynthesis.”

Desynthesis should be understood not as a sort of reflux, but as a movement of drift, like the expression “galactic drift” in the Big Bang theory. The mutual distancing of nebulae here corresponds to the mutual distancing of State, History, and Philosophy and their internal parts from each other; it involves the disarray of the Western system or, more specifically, the breakdown of the system of legitimation of the Western use of the mind, and thus also the dysfunction of the project that refers to that use.

That there is desynthesis can be inferred indirectly from what we might call the Doppler effect of Western civilization, a sort of “redshift” of the “light” emanating from various formations of the objective spirit in which State, History, and Philosophy are variously intertwined.

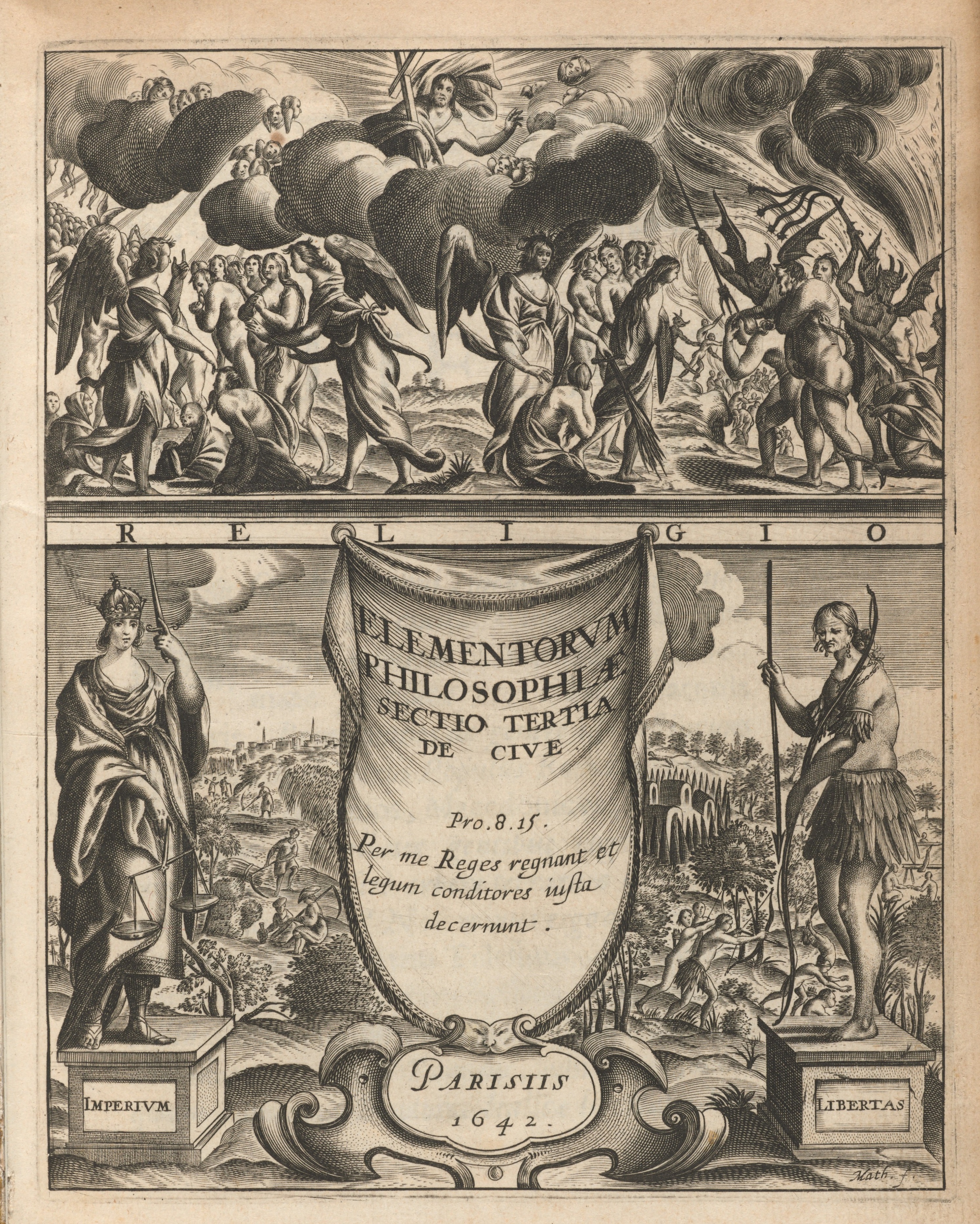

The Doppler effect we are discussing consists, for example, of the recording of the decline of the universalistic model of the European nation-state and, more specifically, in the shift of political and legal investments to the local and territorial, such that statehood seems to produce more as a multiplicity of subversive pushes than as a totalization of collective existence in the ethno-political universality of the nation. To biopolitics as the perfection of Western statehood (the subsumption of life as a biological fact under a power that acts with aesthetic nonchalance) is substituted a sort of geopolitics of territorial instances (the dissemination of the political in the folds of the concrete territoriality and domesticity of existence). Thus, philosophy no longer produces itself as a national educational project, but as a sort of concrete morality that articulates local truths and transient facts for the use of restricted communities. To the university philosophy, which untangled universal teachings for a community without particularistic divisions within it, and thus an ethnically, legally, and politically homogeneous community—which guaranteed the universality of education through a system of public degrees and certificates—is juxtaposed something like a thought that speaks without legitimation, without authority, without certifications, and therefore a thought ‘gone wild,’ or better said, ‘uncivilized,’ which moves from a retreat to territorial belonging rather than from an imperial investiture. To hermeneutics as the perfection of the public philosophy of the late twentieth century is substituted a thought of local instances, a geo-philosophy; to the image of the state professor, the meticulous philologist, the pedagogue, the jealous guardian of orthodoxy, and the accumulator of glosses is juxtaposed, precisely in the sense that it slips to the side, to the right, that of the corsair thinker or, better yet, pirate, vampyr, one who sucks the soul (the juice, the sap of a thought) introducing into bodies (his public image) a spirit that does not correspond (Wild textualism)—to the productivity and commensurability of philosophical work, typical moreover of every homogeneous formation, is substituted a sort of heterogeneous dissemination of the thinking function, a shift in the register of thought from accumulation to expenditure, from education to conspiracy, from capital to treasure, from universal power to transitory munificence. On this basis is forming another economy of thought that alongside the global governance of the mind affixes something like a liberalism or an anarchism of its use, to the catholicism of thought (revelation + tradition + magisterium) juxtaposes a mind unaware of the revelativity of philosophy, disacknowledging the magisterium of clerics and exercising a sort of free examination of tradition: Lutheranism of the mind.

(Finally, the same can be said for historicity. This no longer produces itself as the unisignificance of the world and facts. To the homogeneous and transferable spiritual heritage of nations is substituted the experience of discontinuity and rupture, to universal history the incommensurability of the historical experiences of concrete local communities.)

America Latina: democrazia, populismo e criminalità, di Giorgio Malfatti di Monte Tretto (Eurilink University Press, 2024), ambasciatore e docente universitario, presenta una panoramica esaustiva delle dinamiche politiche, sociali ed economiche dell’America Latina. Il libro si distingue per un’approfondita analisi storica e contemporanea della regione, ponendo l’accento su temi cruciali quali, appunto, la democrazia, il populismo e la criminalità.

America Latina: democrazia, populismo e criminalità, di Giorgio Malfatti di Monte Tretto (Eurilink University Press, 2024), ambasciatore e docente universitario, presenta una panoramica esaustiva delle dinamiche politiche, sociali ed economiche dell’America Latina. Il libro si distingue per un’approfondita analisi storica e contemporanea della regione, ponendo l’accento su temi cruciali quali, appunto, la democrazia, il populismo e la criminalità.

La società aperta e i suoi nemici, pubblicata da Karl Popper in due volumi, tra il 1943 e il 1945, presenta una critica radicale al totalitarismo e difende con passione il valore delle società democratiche e liberali. La sua analisi si estende attraverso la filosofia, la storia e la politica, rendendola una pietra miliare nel pensiero del XX secolo.

La società aperta e i suoi nemici, pubblicata da Karl Popper in due volumi, tra il 1943 e il 1945, presenta una critica radicale al totalitarismo e difende con passione il valore delle società democratiche e liberali. La sua analisi si estende attraverso la filosofia, la storia e la politica, rendendola una pietra miliare nel pensiero del XX secolo. La parte conclusiva dell’opera è dedicata alla difesa della società aperta, che Popper identifica con la democrazia liberale, interpretata non solo come un sistema politico, ma come ethos culturale che valorizza la libertà individuale, il pluralismo e il cambiamento progressivo attraverso metodi pacifici e razionali. La democrazia liberale è innanzitutto un processo. Non è statica né definita da una particolare configurazione istituzionale, ma è un sistema dinamico che consente il cambiamento e l’adattamento. Il filosofo critica le visioni utopiche che vedono la politica come ricerca di un ordine ideale e immutabile. Al contrario, asserisce che la società aperta sia caratterizzata da “una disposizione a imparare dall’errore”, qualità che permette alle società democratiche liberali di correggersi e migliorarsi continuamente. Eleva il concetto di tolleranza a principio fondamentale della società aperta, pur avvertendo contro il “paradosso della tolleranza”: infatti, la tolleranza illimitata può portare alla distruzione della tolleranza stessa, se si permette ai tolleranti di sfruttare la libertà offerta per sopprimere i diritti altrui. In una società aperta, la tolleranza richiede un equilibrio attivo, a cui i limiti sono posti per prevenire l’ascesa di forze intolleranti e autoritarie. Un aspetto risolutivo della democrazia liberale è costituito dall’importanza del disaccordo e del dibattito aperto. Popper sostiene che il progresso scientifico e sociale si verifichi per mezzo di un costante processo di congettura e confutazione, dove le teorie sono proposte, testate e spesso confutate. Analogamente, la democrazia deve operare attraverso un dialogo aperto e critico, in cui le politiche sono proposte, discusse e modificate in risposta ai giudizi e ai cambiamenti delle circostanze. Infine, pone una forte enfasi sui diritti individuali quale fondamento della democrazia liberale. La loro protezione non è solo una questione di giustizia legale o morale ma è essenziale per la creazione di un ambiente in cui gli individui possono pensare, esprimersi e agire senza paura di repressione, considerando ciò essenziale per il mantenimento di una società aperta e per il progresso continuo verso una migliore condizione umana.

La parte conclusiva dell’opera è dedicata alla difesa della società aperta, che Popper identifica con la democrazia liberale, interpretata non solo come un sistema politico, ma come ethos culturale che valorizza la libertà individuale, il pluralismo e il cambiamento progressivo attraverso metodi pacifici e razionali. La democrazia liberale è innanzitutto un processo. Non è statica né definita da una particolare configurazione istituzionale, ma è un sistema dinamico che consente il cambiamento e l’adattamento. Il filosofo critica le visioni utopiche che vedono la politica come ricerca di un ordine ideale e immutabile. Al contrario, asserisce che la società aperta sia caratterizzata da “una disposizione a imparare dall’errore”, qualità che permette alle società democratiche liberali di correggersi e migliorarsi continuamente. Eleva il concetto di tolleranza a principio fondamentale della società aperta, pur avvertendo contro il “paradosso della tolleranza”: infatti, la tolleranza illimitata può portare alla distruzione della tolleranza stessa, se si permette ai tolleranti di sfruttare la libertà offerta per sopprimere i diritti altrui. In una società aperta, la tolleranza richiede un equilibrio attivo, a cui i limiti sono posti per prevenire l’ascesa di forze intolleranti e autoritarie. Un aspetto risolutivo della democrazia liberale è costituito dall’importanza del disaccordo e del dibattito aperto. Popper sostiene che il progresso scientifico e sociale si verifichi per mezzo di un costante processo di congettura e confutazione, dove le teorie sono proposte, testate e spesso confutate. Analogamente, la democrazia deve operare attraverso un dialogo aperto e critico, in cui le politiche sono proposte, discusse e modificate in risposta ai giudizi e ai cambiamenti delle circostanze. Infine, pone una forte enfasi sui diritti individuali quale fondamento della democrazia liberale. La loro protezione non è solo una questione di giustizia legale o morale ma è essenziale per la creazione di un ambiente in cui gli individui possono pensare, esprimersi e agire senza paura di repressione, considerando ciò essenziale per il mantenimento di una società aperta e per il progresso continuo verso una migliore condizione umana.