Taken from my lectures as a Teaching Fellow in International Law, these reflections highlight how State sovereignty and International Law are profoundly influenced by globalization, economic integration and digital technologies, raising fundamental questions about global governance, State autonomy and the adaptation of legal structures to new economic and technological realities.

Part VI

On Hegel again

The market narrative transforms into a tale of synchronism, capturing the temporal reality of individuals and propelling them into an electronic and offshore dimension where spatial and State boundaries dissolve. This process occurs in a context where anchorage becomes purely formal on a legal level and deeply meaningful economically. At the heart of market dynamics lies its very essence, outlined by a sphere where competition and the repetition of competitive challenges find their place. However, the existence of the market presupposes a legal and institutional framework, manifested through a set of laws, regulations, principles, and practices, thus inviting the State to participate, in a relationship where the market law becomes a matter for the State, sometimes in competition with other State entities.

In the global context, the uninterrupted presence of financial technology dominates, opening doors to new possibilities. The modern lex mercatorum operates in a globally undifferentiated and spatially de-qualified market, but still characterized by the political division into different States, aiming to overcome legal discontinuities and regulate uniformly the spatial deformity of territories, reconciling the needs of the stateless mercantile society with those of national States.

This situation introduces a dilemma between universality and multiplicity, renewing the concept of nomos, which no longer identifies with the unification of law and territory, but reflects the interdependence and independence of actors from the State, highlighting a permanent friction between States and markets. Consequently, the law finds itself weakened between the limited territoriality of norms and the universality of economic relations, challenging the old narratives of State.

This new dynamic sets Earth and Sea as symbols of the different potentialities of existence and contrasting scenarios of human history, where the Earth is seen as the mother of law and the Sea as a domain free from juridical and spatial boundaries, symbolizing infinite freedom.

Finally, the ancient act of land occupation, nomos, clashes with the universalism of economic exchanges, leading to the necessity of a new legal category that can rationalize the chaotic space of globalization. This need leads to the conception of a law that transcends terrestrial constraints, offering new perspectives to regulate the vast and indeterminate space of major economic exchanges, with technology emerging as a regulating principle. In this scenario, the law adapts to regulate the digital and transnational economy, challenging the traditional opposition between territorial law and global economy.

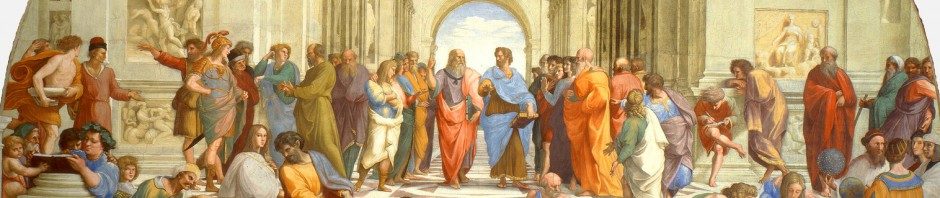

The rhetorical figure of the owl associated with Minerva is often invoked to attribute to Hegel and his philosophical thought a belated, almost posthumous role: that of intervening in reality only to confirm and ratify events that have already occurred. In this interpretation, Hegel’s philosophy would be reduced to an ideology that retroactively legitimizes what has already happened, thus representing a historical narrative written by the victors, emerging at twilight similarly to the appearance of an owl.

However, Hegel’s assertion that “what is real is rational, and what is rational is real” invites us to view the present through a conceptual lens, allowing the intellect to become an active agent in shaping reality. Consequently, the symbolism of the owl should not be interpreted as mere legitimization of the existing state of affairs, but rather as a call for thought to embark on a gradual and profound process of understanding, in order to mould the future. The task of conceptual elaboration thus proves essential for mediating and resolving conflicts, organizing them into a dynamic unity that, despite its cohesion, does not erase the distinctive peculiarities of each position.

Hegel thus emerges as the architect of thoughtful mediation, strongly opposing any attempt at immediate or superficial solutions. He criticizes the pursuit of intuitive and spontaneous genius, as well as rejects any form of mystical ecstasy or charisma, abhorring the presumption of those who claim to be direct spokespersons of divinity or interpreters of the absolute through altered states of consciousness. Dialectics, for Hegel, is precisely that method of thought capable of organizing and synthesizing conflict through careful and gradual elaboration, merging universality with the vital needs of every single component.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nel suo Discorso sull’origine e i fondamenti della diseguaglianza tra gli uomini, pubblicato nel 1755, esamina le radici profonde e le conseguenze della diseguaglianza umana, presentando una critica serrata alle società moderne, basate sulle istituzioni e sulla proprietà privata. Quest’opera si distingue quale uno dei testi fondamentali nella storia della filosofia politica e sociale, proponendo una riflessione profonda che interpella ancora oggi il lettore su temi di bruciante attualità.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nel suo Discorso sull’origine e i fondamenti della diseguaglianza tra gli uomini, pubblicato nel 1755, esamina le radici profonde e le conseguenze della diseguaglianza umana, presentando una critica serrata alle società moderne, basate sulle istituzioni e sulla proprietà privata. Quest’opera si distingue quale uno dei testi fondamentali nella storia della filosofia politica e sociale, proponendo una riflessione profonda che interpella ancora oggi il lettore su temi di bruciante attualità.

Utopia, pubblicata nel 1516 da Thomas More, è un’opera che non solo ha introdotto un nuovo genere letterario, quello della letteratura utopica, ma ha anche offerto uno spaccato profondo delle tensioni politiche e filosofiche del Cinquecento inglese ed europeo. Attraverso la descrizione di un’isola immaginaria e della sua società ideale, More esplora temi di giustizia sociale, organizzazione politica e morale individuale.

Utopia, pubblicata nel 1516 da Thomas More, è un’opera che non solo ha introdotto un nuovo genere letterario, quello della letteratura utopica, ma ha anche offerto uno spaccato profondo delle tensioni politiche e filosofiche del Cinquecento inglese ed europeo. Attraverso la descrizione di un’isola immaginaria e della sua società ideale, More esplora temi di giustizia sociale, organizzazione politica e morale individuale.