From the Crisis of the Papacy to Boniface VIII

From the mid-13th century, the papacy fell into a deep crisis, evident in the short duration of the pontificates themselves, which were often interrupted by long periods of vacancy.

The spirit that characterized the last part of the 13th century was one of political exhaustion and religious exaltation, marked by spiritual struggles within the Franciscan Order and an apocalyptic expectation of a “papa angelicus.” In the conclaves, efforts were made to find an exceptional candidate who could meet these expectations. Such a candidate was found in Pietro Angeleri da Morrone, a hermit from Abruzzo, who took the name Celestine V (1294). His pontificate lasted only six months and ended with his abdication.

In his place, Boniface VIII (1294–1303) was elected, bringing back to the political scene a capable and resolute figure, determined to restore the traditional power of the papacy at a time when kingdoms were striving for autonomy, foremost among them France.

However, he lacked foresight: he failed to understand that times had changed. His pontificate was thus characterized by conflict with Philip IV, known as Philip the Fair.

Philip IV was engaged in a struggle with England over the Scottish throne. Boniface VIII saw this fratricidal conflict as a sign of the decline of “Christianitas.” After unsuccessful appeals for reconciliation, he issued the bull Clericis laicos in 1296, forbidding the French clergy from paying taxes to the king, thereby depriving him of the resources needed to continue the war. In response, Philip IV banned any export of money from France, cutting off most of the Apostolic Chamber’s revenues. Boniface VIII was forced to yield.

The peace, however, was short-lived. Philip IV later had a papal legate imprisoned. Boniface VIII summoned him before his tribunal with the bull Ausculta, fili, which Philip IV rejected. In response, Boniface VIII issued the famous bull Unam Sanctam, asserting the theory of the two swords and the supremacy of the Sacerdotium over the Regnum. In retaliation, Philip IV launched a defamatory campaign against the pope. Meanwhile, in Anagni, Boniface VIII was preparing to excommunicate Philip IV when the latter, with a small force of soldiers, attacked the pope and held him prisoner in his own residence, from which he was freed two days later by the local population.

Yet, the grave offense against the pope went unpunished—a sign that the papal figure had declined in stature and that religion had become a mere political matter.

This marked the end of Christianitas.

Boniface VIII returned to Rome, where he died shortly thereafter, along with the dreams of papal dominion over the world. With Boniface VIII, the universal supremacy of the papacy definitively came to an end.

The Consequences of a Slap

The process of subordinating the Church to the state, which began with Constantine, deepened under Charlemagne and the Ottonians, was interrupted and reversed by Gregory VII, the Concordat of Worms, and Innocent III: imperial theocracy gave way to papal theocracy.

However, with the significant attack on Boniface VIII (1308) by Philip IV of France—the so-called Slap of Anagni—the decline of papal power began. It faced strong opposition from the emerging European states.

As a result, in the late Middle Ages, a clear opposition to and rejection of papal claims to temporal power over states took shape, while the pope’s authority came to be regarded increasingly as a spiritual one concerning salvation.

Within this framework, three trends emerged: the governance of the Church in its temporal expression gradually passed to the principes, while the clergy in public and judicial administrations were replaced by lay officials.

Thus, a new bureaucratic and administrative class was established, upon which the clergy increasingly depended to achieve its objectives. However, this was not a secularization of state life but rather an assertion of independence from papal authority.

The superiority of the gladius spiritualis et materialis was no longer accepted sic et simpliciter but was contested and rejected.

The drive for independence from papal power was also fueled by excessive hierocratic claims, which were heightened precisely by this emerging spirit of autonomy from ecclesiastical authority. However, this was still not a full secularization of power but rather a demand for access to the sacred temporal authority of the Church.

The vision of the world as the historical organization of the divine had not yet faded. Nevertheless, the legitimacy of the Church’s possession and ownership of property was increasingly questioned, as it became entangled in a process of administrative and managerial autonomy within cities.

A significant issue in this context was the vexata quaestio that divided the forces within the Church: Had Christ owned and possessed his garments, or had he merely used them?

The Franciscans upheld the position of mere usus (use), while the theorists of poverty, contesting the Church’s ownership of goods, argued that these should be maintained under state authority.

From this overall picture, it is clear that the political resurgence of temporal power—seeking to reclaim positions lost due to the rise of hierocracy—was extending ever further into temporal and ecclesiastical affairs, asserting its administrative rights and autonomy. This stance soon extended to spiritual matters as well, now seen as part of the common good.

The Papacy in Avignon

After the death of Boniface VIII, French influence over the papacy grew significantly. Under pressure from France, numerous French cardinals were appointed to the College of Cardinals. Consequently, it was inevitable that during this period, there were several French popes.

The first in this series was Clement V (1305–1314), who succeeded Benedict XI (1303–1304), whose pontificate was brief and who, in turn, had succeeded Boniface VIII.

Clement V deemed it appropriate to move the papal seat from Rome to Avignon, which, along with the County of Venaissin, belonged to the Papal States. This decision was due both to the unstable situation in the Papal States and Italy and to his belief that from Avignon, he could more effectively mediate between France and England, which were vying for the Scottish throne.

Soon, however, from 1309 onward, Avignon became the permanent seat of the papacy for approximately seventy years. This was a clear sign that the balance of power had shifted toward France: the autonomy of the Church, established by Gregory VII’s Dictatus papae (1075), reaffirmed by the Concordat of Worms (1122), and embodied by Innocent III, was entirely dismantled.

During these seventy years (1309–1378), the papacy became a tool of power in the hands of the French monarchy. Clement V proved highly submissive to Philip IV, who compelled him to annul the bull Unam Sanctam, suppress the Templars—a decision confirmed at the Council of Vienne (1312)—and, ultimately, open a posthumous trial against Boniface VIII.

Only with the ascension of Gregory XI (1370–1378), under popular pressure led by figures such as St. Catherine of Siena and St. Bridget of Sweden, was the papacy transferred back to Rome. From this moment onward, the modern papacy would take shape.

The Consequences of the Avignon Exile

When evaluated as a whole, the Avignon exile caused immense and irreparable damage to the papacy and the Church: it deeply shook the confidence it had enjoyed up until the time of Innocent III, led to the Western Schism, which lasted forty years, fostered conciliarism, and ultimately laid the groundwork for the schism triggered by the Lutheran Reformation.

Indeed, French influence over the Avignon papacy had disastrous repercussions during the pontificate of John XXII (1316–1334) concerning papal policy toward the German Empire. In 1323, the pope deposed Emperor Louis IV of Bavaria, adopting a hostile stance against him and thus aligning himself with French interests.

This act had serious consequences, placing Germany in strong opposition to the papacy and leading to fatal outcomes for the latter.

For the first time in history, the imperial counterattack did not target a specific pope but rather the very institution of the papacy, whose excessive power had now exceeded all bounds.

In 1324, Emperor Louis IV appealed to a council against John XXII. He was joined by all religious figures opposed to the pope, including Marsilius of Padua and John of Jandun, who developed a revolutionary theory that would give rise to conciliarism and fuel the Protestant critique of the papacy—one that persists to this day.

This theory, outlined in the book Defensor Pacis, questioned the hierarchical structure of the Church and proposed a democratic foundation instead. It denied the divine origin of papal primacy and attributed sovereign power in the Church to the people. Thus, there was no inherent priority of the clergy over the laity. The pope, bishops, and clergy were seen as fulfilling a mandate given to them by the Congregatio fidelium, represented by an ecumenical council.

This vision of the Church reduced the pope to a mere executive organ of the council, making him subordinate to it and obliging him to obey its decisions.

This theory, which subjected the papacy to the council, became known as conciliarism and found its full realization at the Council of Constance with the bull Haec sancta.

The Avignon period was also marked by a significant increase in fiscal policies, carried out through highly questionable and often extreme measures, leading to widespread disorder and scandal. Taxes were sometimes collected through the granting of privileges and papal favors, and at other times, they were extorted under the threat of censure or excommunication.

Such practices intensified hostility toward the Curia, particularly in Germany, where opposition was fueled by the pope’s anti-German stance against Louis IV of Bavaria. Over time, this resentment grew, reaching its peak in the Gravamina Nationis Germanicae and later influencing the Reformation of the 16th century.

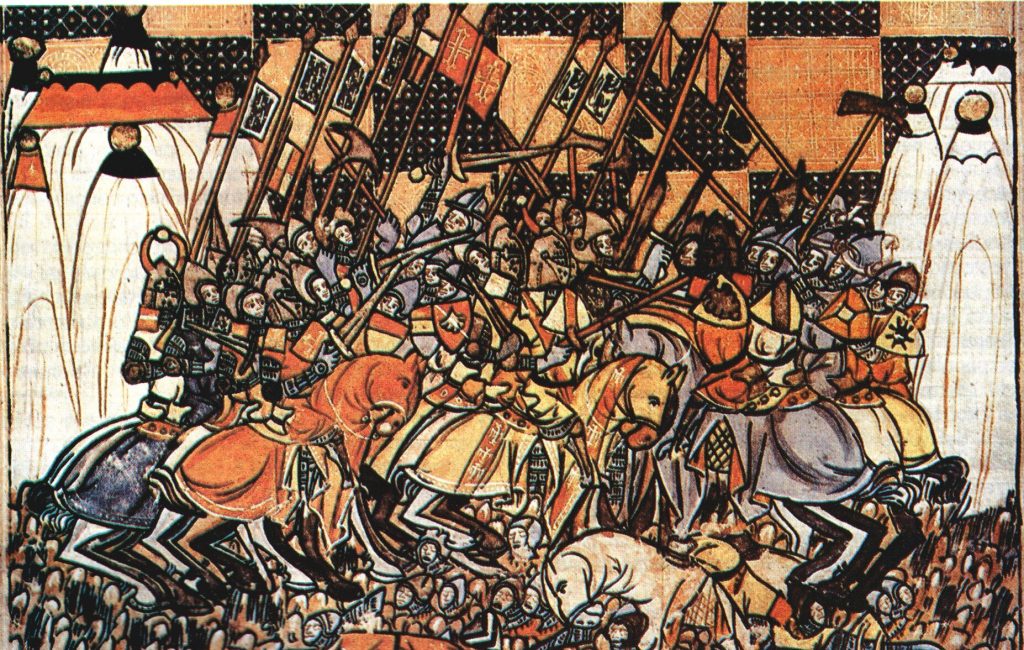

The Council of Vienne and the Templars

During the pontificate of Clement V, a weak French pope completely at the mercy of the arrogant and demonic Philip IV, the shameful suppression of the Templars took place.

Founded during the Crusades for the defense of the Holy Land and Jerusalem by Hugues de Payens and Godfrey of Saint-Omer, the Templars lived under a rule drafted by St. Bernard. In addition to the three religious vows, they took a fourth vow—to defend Jerusalem.

They were led by the Grand Master, forming an ecclesiastical knighthood distinguished by heroic actions. Over time, they became financial intermediaries between the East and the West.

Philip IV, arrogant and envious of their autonomy, as well as covetous of their wealth, orchestrated slanderous accusations against them. He had 2,000 Templars arrested, confiscated their assets, and entrusted them to the Inquisitor of France, who was also his confessor.

This infamous conspiracy gained a legal form through the Council of Vienne (1312). What followed was a true massacre of the Templars, without the cowardly and feeble Clement V—merely a puppet in the hands of the king—daring to protest.

Thus ended a glorious institution that had covered itself in honor and had always faithfully served the Church and Christianity.

The Western Schism

After the death of Gregory XI (1370–1378), the last of the Avignon popes who, shortly before his death and under popular pressure—including that of St. Catherine of Siena and St. Bridget of Sweden—returned the papal seat to Rome, a new pope was elected by a College of Cardinals composed of 16 cardinals, 11 of whom were French.

Fear that another French pope would be elected and that Rome would once again be abandoned led the people to exert strong and violent pressure on the cardinals to elect a Roman or at least an Italian pope. Intimidated, they elected the Cardinal of Bari, who took the name Urban VI, to whom they swore allegiance.

However, after three months—due to his despotic and fanatical character, which some believed had been altered by the papal election itself; because the election was thought to be invalid as it had been carried out under threat and violence; and finally, due to the strong and self-serving pressures from France—the cardinals abandoned Urban VI. In Fondi, under French protection, they elected another pope, a cousin of the King of France, who took the name Clement VII (1378–1397). He attempted to take Rome by force but failed and instead settled in Avignon.

From that moment, there were two popes, creating a deep and scandalous rift in Christianity and the West. This division extended even to dioceses and parishes and lasted for forty years.

Both popes considered themselves legitimate and viewed the other as an usurper. They did not hesitate to excommunicate each other’s followers, so much so that, in a short time, all of Europe found itself excommunicated.

The University of Paris proposed three possible solutions to this shameful and incredible situation:

- The via cessionis, meaning voluntary abdication.

- The via compromissi, referring the matter to an arbitration tribunal.

- The via concilii, resolving the issue through a council.

Unfortunately, all efforts were in vain. The two popes established their own pontifical courts with full administrative and organizational structures, and upon their deaths, each had successors.

The Council of Constance and Conciliarism

After thirty years of failed attempts to restore order—since neither pope was willing to abdicate or submit to arbitration—the idea that an ecumenical council could resolve the issue gained traction (the third option).

Thus, in 1409, a council was convened in Pisa, where both popes were deposed, and a new one was elected—Alexander V—who had a brief reign before being succeeded by John XXIII. However, Gregory XII and his rival Benedict XIII refused to comply with the council’s decisions, leading to a situation where there were three popes at once—all simultaneously legitimate and illegitimate.

John XXIII was supported by the German king Sigismund, who, in an effort to put an end to this scandalous and disgraceful situation, was authorized by John XXIII to convene a council in Constance. John XXIII secretly hoped to be recognized as the legitimate pope.

However, when it was decided—so as to neutralize the Italian faction’s numerical superiority—that voting would be conducted not per capita singulorum but per nationes, John XXIII realized his chances were gone. He fled during the night, hoping that the council, in his absence, would be suspended.

But the emperor took charge of the situation, and with the support of the controversial conciliar decree Haec sancta (fifth session), which declared the superiority of the council over the pope, the proceedings resumed, focusing on three main issues:

- The resolution of the schism.

- The condemnation of the heresies of Wycliffe and Hus (eighth and fifteenth sessions).

- The reform of the Church in capite et membris (in both head and members).

Additionally, with the decree Frequens (thirty-ninth session), it was established that councils would be convened regularly every 5, 7, and 10 years, effectively making the council a supervisory body over the papacy.

The Council of Constance lasted four years, attended by over 300 bishops and prelates, 30 cardinals, and 33 archbishops, along with many representatives of the political nobility. Five nations were present: Italy, France, Spain, Germany, and England.

As for the three rival popes: John XXIII was arrested; Gregory XII, already in his nineties, abdicated; and Benedict XIII was deposed as a heretic and withdrew to Spain, where he died.

Finally, a new pope, Martin V (1417–1431), was elected.

The Roots of Conciliar Theories

Beyond historical aspects, conciliarism has its roots in early medieval canon law. To ensure the libertas ecclesiae from the emperor and the nobility, canon law had conceived of the Church as a “corporation” of individuals with the right to act and sovereign capacity.

According to this theory, the bishop and the chapter formed a corporation capable of autonomous action. However, the bishop, as caput, was bound to the totum, without which he lost his corporate identity and thus his legal capacity. This led to significant axioms such as “Totum est maior sua parte”, emphasizing the superiority of the totum over the caput.

Similarly, the College of Cardinals viewed its relationship with the pope. Under this corporative conception, the pope received his powers from the College, making him an authorized administrator of those powers.

Alongside the corporate theory, a legal-personalistic conception emerged. This distinguished between potestas ordinis, transmitted by Christ to all the apostles, and potestas iurisdictionis, entrusted only to Peter. As a result, the Church’s jurisdictional power came from the pope rather than from the corporation. Thus, in papal elections, the College did not transfer its own powers to a delegate but simply elected the person who held the plenitudo potestatis conferred by Christ upon Peter and his successors. Therefore, Christ, not the College, was the true holder of ecclesiastical power.

This issue, dormant during the struggle between regnum and sacerdotium, resurfaced vigorously during the period of conciliarism.

Thus, Haec sancta was not a coup but rather a canonical application of corporative theory, which reached its extreme in the Tres veritates fidei catholicae, which proclaimed:

- The superiority of the council over the pope.

- The pope’s inability to transfer or suspend a council without conciliar approval.

- That any stubborn opposition to these propositions was to be considered heresy.

Jan Hus and John Wycliffe

Jan Hus was born in Husinec, southern Bohemia, in 1370. At the age of 30, he was ordained a priest and, around 1400, became acquainted with the ideas of the Englishman John Wycliffe, who, since 1374, had launched violent attacks against the methods of the Avignon papacy, the wealth of prelates, and the hierarchy.

In response to this decadence, Wycliffe proposed his spiritualistic vision of the “Church of the Predestined,” which should renounce all possessions and live in apostolic poverty. In this ideal Church, according to Wycliffe, only those in a state of grace could belong; anyone in mortal sin could not be part of it, let alone lead the Christian community, whether in the Church or in the state. A pope, bishop, or any clergyman in mortal sin had no authority; likewise, rulers lost their legitimacy.

This theory was very similar, if not identical, to the Donatist heresy, which had already been thoroughly refuted by St. Augustine in the 4th and 5th centuries.

Although Wycliffe’s intentions were good, his theory, if applied, was highly destabilizing to both religious and political authority. After all, who could ever claim to be in a state of grace? Who could be so pure, holy, and perfect as to be considered a permanent member of such a Church and society? Like Donatus, Wycliffe fell into an excess of ascetic rigorism.

Jan Hus embraced and disseminated Wycliffe’s ideas, gaining widespread support not only for religious and ascetic reasons but also due to political motivations. In Bohemia, most prelates were German, so his harsh criticism of them fueled a strong anti-German sentiment, which mobilized all of Bohemia in support of Wycliffe’s religious ideas, championed by Hus.

However, when the German Archbishop of Prague, entrusted by Pope Alexander V with handling the delicate religious issue, took severe repressive measures against the heresy, his actions were interpreted as purely political. Hus refused to submit to the German prelate and appealed to Pope John XXIII, as did the archbishop.

The pope, after summoning Jan Hus to Rome in vain, excommunicated him. Later, he was deceitfully imprisoned by the cardinals, put on trial, and condemned to death by burning as a heretic after repeatedly and unsuccessfully being urged to recant his beliefs. The Council of Constance addressed his case, as well as that of Wycliffe, and in its eighth and fifteenth sessions, condemned both their theories as heretical.

On December 17, 1999, in a speech to participants at an international conference on Jan Hus, Pope John Paul II expressed understanding for this thinker, reassessing his moral character and subtly condemning the cruel injustices he suffered at the hands of the Church.

The Councils of Basel, Ferrara, and Florence (1431–1442)

In accordance with the decree Frequens issued at the Council of Constance, five years after its closure (1418), Martin V convened a council in Pavia, which was later moved to Siena due to an outbreak of plague. However, due to low participation, it was postponed to Basel in 1431. That year, it was opened by Eugene IV, who had just succeeded Martin V.

The participants, empowered by the Haec sancta decree, claimed supreme decision-making authority and significantly curtailed papal power.

To put an end to ongoing conflicts, in 1437, Eugene IV transferred the council to Ferrara. During this time, an attempted schism occurred, which fortunately failed—along with conciliarism itself, though its influence persisted in a latent and feared form.

The council resumed in Ferrara in 1438 but was almost immediately moved to Florence due to the threat of plague, continuing there from 1439 until its closure in 1442.

The primary goal of the council was the reunification of the Eastern and Western Churches, requiring clarification on several controversial points:

- The issue of the Filioque.

- The primacy of the pope.

- The doctrine of Purgatory.

- The Latin use of unleavened bread and other liturgical matters.

The underlying motivation for the union was the urgent need for assistance against the Turks, who were threatening Constantinople. Only a strong crusade could save the city from its impending doom.

After long discussions, an agreement was reached in the decree Laetentur coeli, but it lasted only briefly. Strong opposition awaited its supporters upon their return to Constantinople, and the West ultimately refused to provide military aid, abandoning the city to the Turks. In 1453, Constantinople was conquered and destroyed, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire.

The legacy of Constantinople was assumed in 1459 by Moscow, which soon came to be designated as the “Third Rome.”

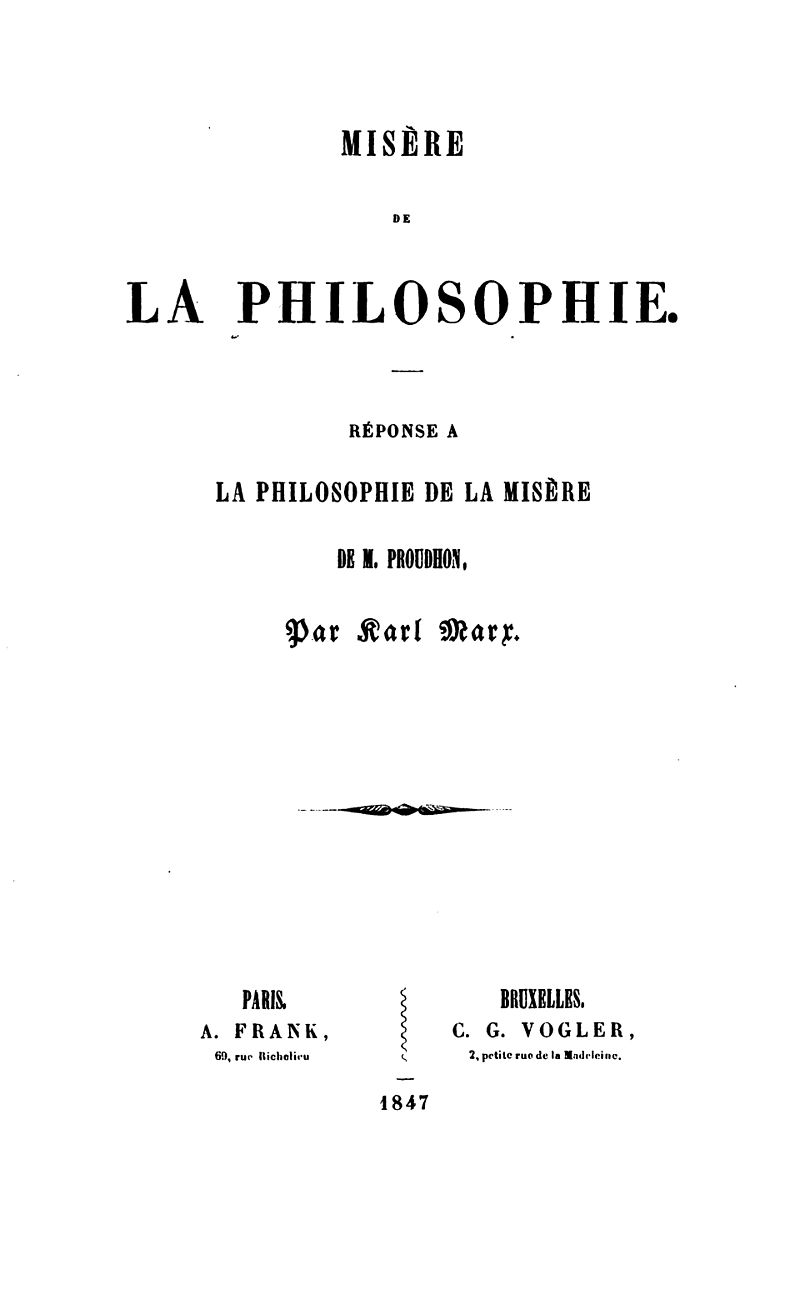

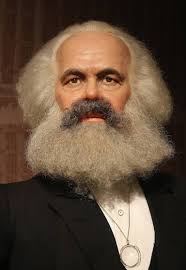

La miseria della filosofia di Karl Marx, pubblicata nel 1847, è una delle opere più significative del pensiero marxiano, imperniata su una critica serrata alle teorie di Pierre-Joseph Proudhon e alla sua Philosophie de la misère (1846). Nella prima metà del XIX secolo, l’espansione del capitalismo stava generando una rapida crescita economica, accompagnata da disuguaglianze sempre più marcate tra le classi sociali. La borghesia industriale si affermava come classe dominante, mentre la classe operaia, vittima di sfruttamento e di dure condizioni di lavoro, cominciava a organizzarsi per rivendicare diritti e condizioni più eque. In questo contesto, il socialismo emergeva come un movimento articolato in diverse correnti e interpretazioni. Proudhon, tra i principali teorici del socialismo francese, tentava di proporre soluzioni ai problemi della società capitalista, combinando filosofia, economia e morale. Tuttavia, la sua opera, pur animata da uno spirito progressista, fu considerata da Marx teoricamente incoerente e insufficiente per affrontare le contraddizioni del capitalismo. Esiliato a Bruxelles, Marx stava sviluppando il suo materialismo storico, approfondendo l’analisi sull’economia politica e sulla storia. La critica a Proudhon costituì per lui l’occasione di affinare il proprio pensiero, differenziando il socialismo scientifico da quello utopistico.

La miseria della filosofia di Karl Marx, pubblicata nel 1847, è una delle opere più significative del pensiero marxiano, imperniata su una critica serrata alle teorie di Pierre-Joseph Proudhon e alla sua Philosophie de la misère (1846). Nella prima metà del XIX secolo, l’espansione del capitalismo stava generando una rapida crescita economica, accompagnata da disuguaglianze sempre più marcate tra le classi sociali. La borghesia industriale si affermava come classe dominante, mentre la classe operaia, vittima di sfruttamento e di dure condizioni di lavoro, cominciava a organizzarsi per rivendicare diritti e condizioni più eque. In questo contesto, il socialismo emergeva come un movimento articolato in diverse correnti e interpretazioni. Proudhon, tra i principali teorici del socialismo francese, tentava di proporre soluzioni ai problemi della società capitalista, combinando filosofia, economia e morale. Tuttavia, la sua opera, pur animata da uno spirito progressista, fu considerata da Marx teoricamente incoerente e insufficiente per affrontare le contraddizioni del capitalismo. Esiliato a Bruxelles, Marx stava sviluppando il suo materialismo storico, approfondendo l’analisi sull’economia politica e sulla storia. La critica a Proudhon costituì per lui l’occasione di affinare il proprio pensiero, differenziando il socialismo scientifico da quello utopistico. Marx accusò Proudhon di un approccio superficiale e idealistico, basato su una presunta scienza universale dell’economia fondata su princìpi di giustizia eterna. Per esempio, Proudhon proponeva una “banca del popolo” per offrire credito senza interessi e un sistema di scambio fondato sul valore del lavoro. Marx stroncava tutto ciò, sostenendo che il problema centrale risiedesse nella struttura stessa del capitalismo, basata sulla proprietà privata dei mezzi di produzione e sullo sfruttamento del lavoro salariato.

Marx accusò Proudhon di un approccio superficiale e idealistico, basato su una presunta scienza universale dell’economia fondata su princìpi di giustizia eterna. Per esempio, Proudhon proponeva una “banca del popolo” per offrire credito senza interessi e un sistema di scambio fondato sul valore del lavoro. Marx stroncava tutto ciò, sostenendo che il problema centrale risiedesse nella struttura stessa del capitalismo, basata sulla proprietà privata dei mezzi di produzione e sullo sfruttamento del lavoro salariato.